Joe Louis at Bushy Park

Joe Louis (1914 – 1981) was one of the best boxers the world has ever seen – even Muhammad Ali called him ‘the greatest heavyweight fighter ever’.

Nicknamed the ‘Brown Bomber’, Joe was a trailblazer who fought discrimination both in the ring and outside of it.

Today, he is remembered as one of the first black sportsmen to transcend the colour barrier in a divided America, gaining acclaim from black and white audiences alike.

During the Second World War, Joe made a very special appearance at Bushy Park. This was an event that locals would remember for decades to come…

Who was Joe Louis?

Joe Louis was one of eight siblings born into a large family in rural Alabama, where his grandparents had once been enslaved. When he was a child, his family moved north. They were part of the ‘Great Migration’ which saw many African American families move away from the south, where work was hard to find but discrimination was not.

The family settled in Chicago, where Joe took a range of jobs to support his family during the Great Depression – he trained as a cabinet maker, worked at a vegetable market and even delivered ice.

When he was eleven years old, Joe was introduced to boxing. He was tall, strong and fast – it was immediately obvious that he had skill in the ring. Before long, he was making a name for himself as an amateur, winning the vast majority of his matches – even against more experienced opponents.

Joe soon gained a manager and a trainer who helped him move into professional boxing. This team made it clear that he was going to face discrimination – they told Joe that he would be held to higher standards than white sportsmen, so it was vital that he behaved with dignity and projected a clean-living persona.

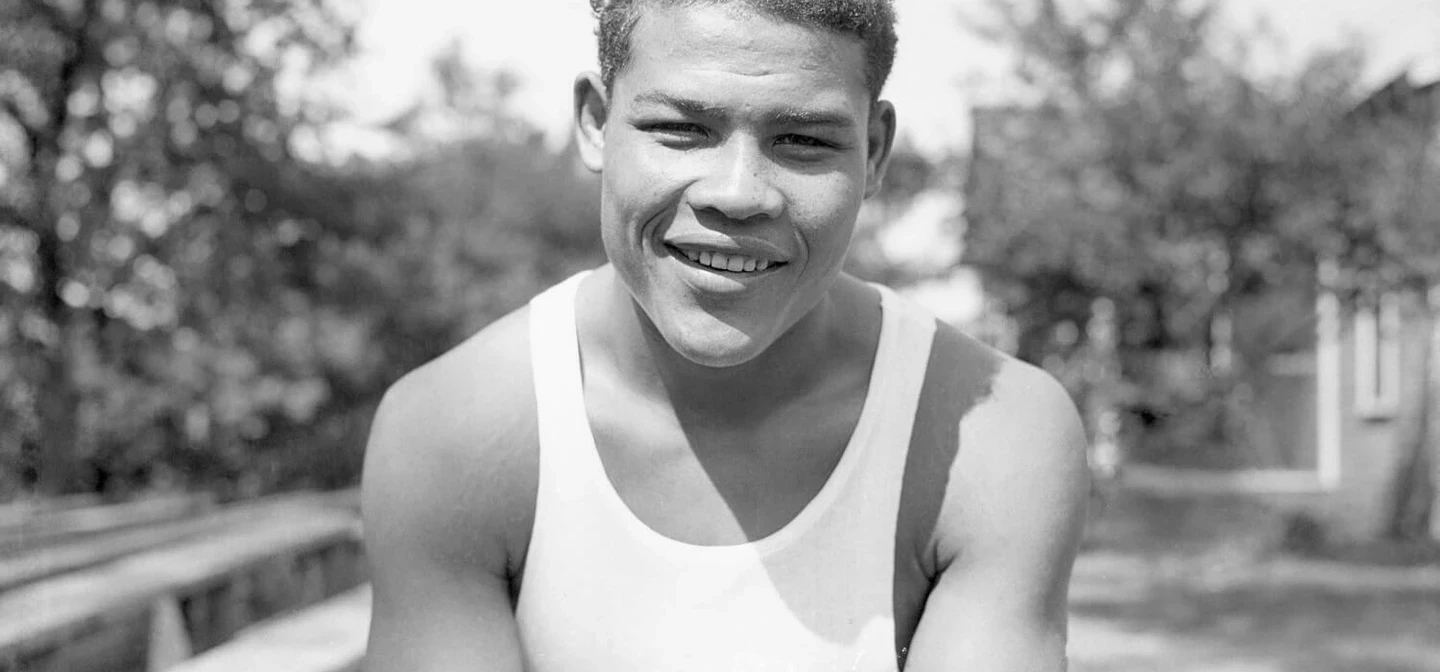

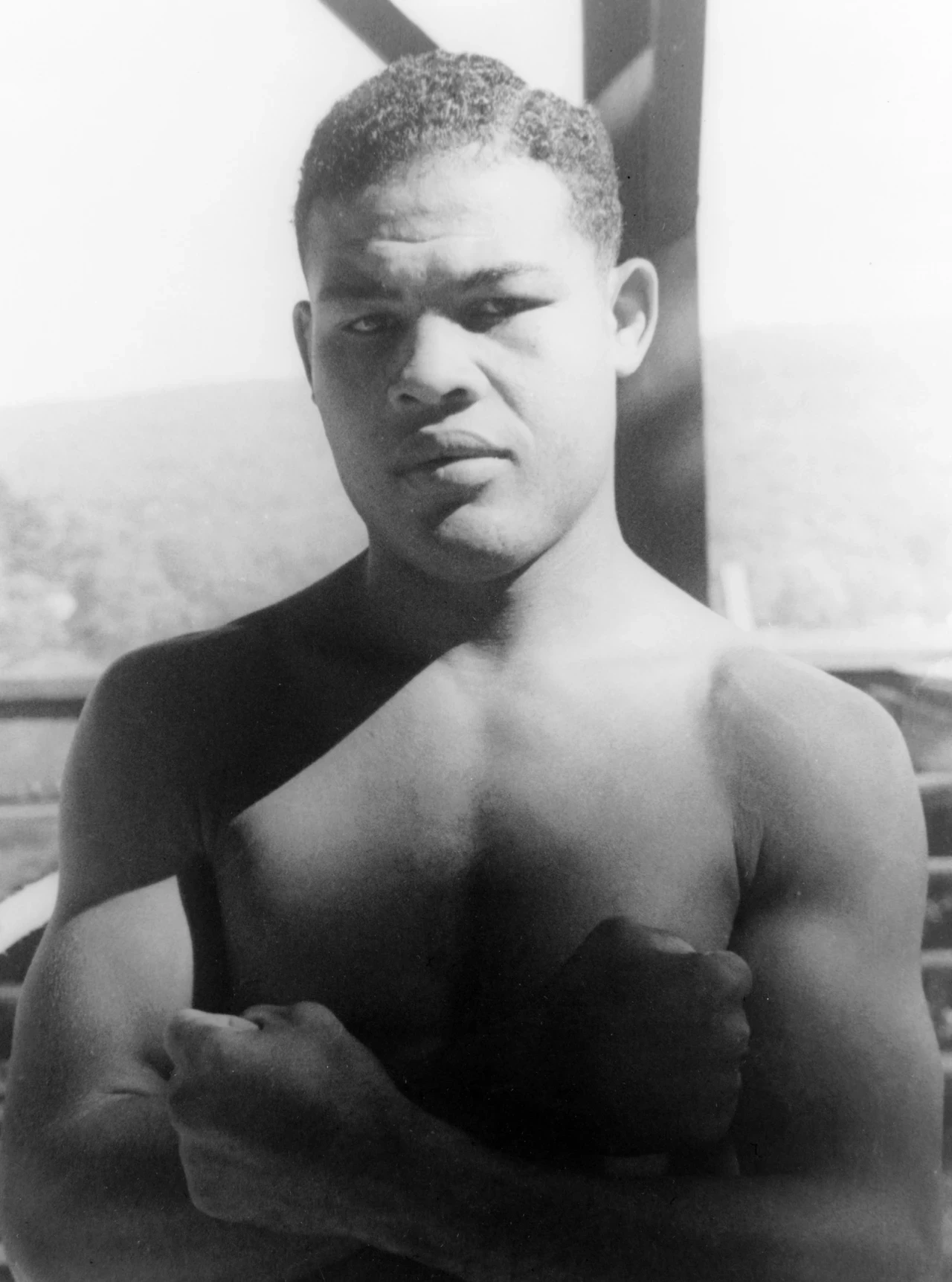

(Image: Joe Louis photographed by Carl Van Vechten in 1941 © US Library of Congress)

On several occasions, Joe used his growing influence to push against racial discrimination, on one occasion insisting that black journalists were given good seats at matches, as only white journalists had been allowed to sit ringside before this. He also donated money to charitable causes and bought his mother a house.

Joe continued to work his way through the ranks, beating opponents across America and becoming a national hero – particularly in the black community. The writer Langston Hughes said:

'Each time Joe Louis won a fight in those depression years, even before he became champion, thousands of black Americans […] would throng out into the streets all across the land to march and cheer and yell and cry because of Joe’s one-man triumphs. No one else in the United States has ever had such an effect on Negro emotions – or on mine.'

'King Joe'

In 1937, Louis reached the pinnacle of his profession, becoming the heavyweight champion of the world. Malcolm X said at the time:

'Every negro boy who could walk wanted to be the next Brown Bomber.'

Joe Louis was now a major celebrity – he earned huge sums of money, appeared in films, set up his own baseball team and even inspired a song by Count Basie called ‘King Joe’, performed by Paul Robeson.

(Image: Count Basie and Paul Robeson’s record ‘King Joe’ © National Museum of African American History and Culture)

How did Joe Louis fight fascism in the ring?

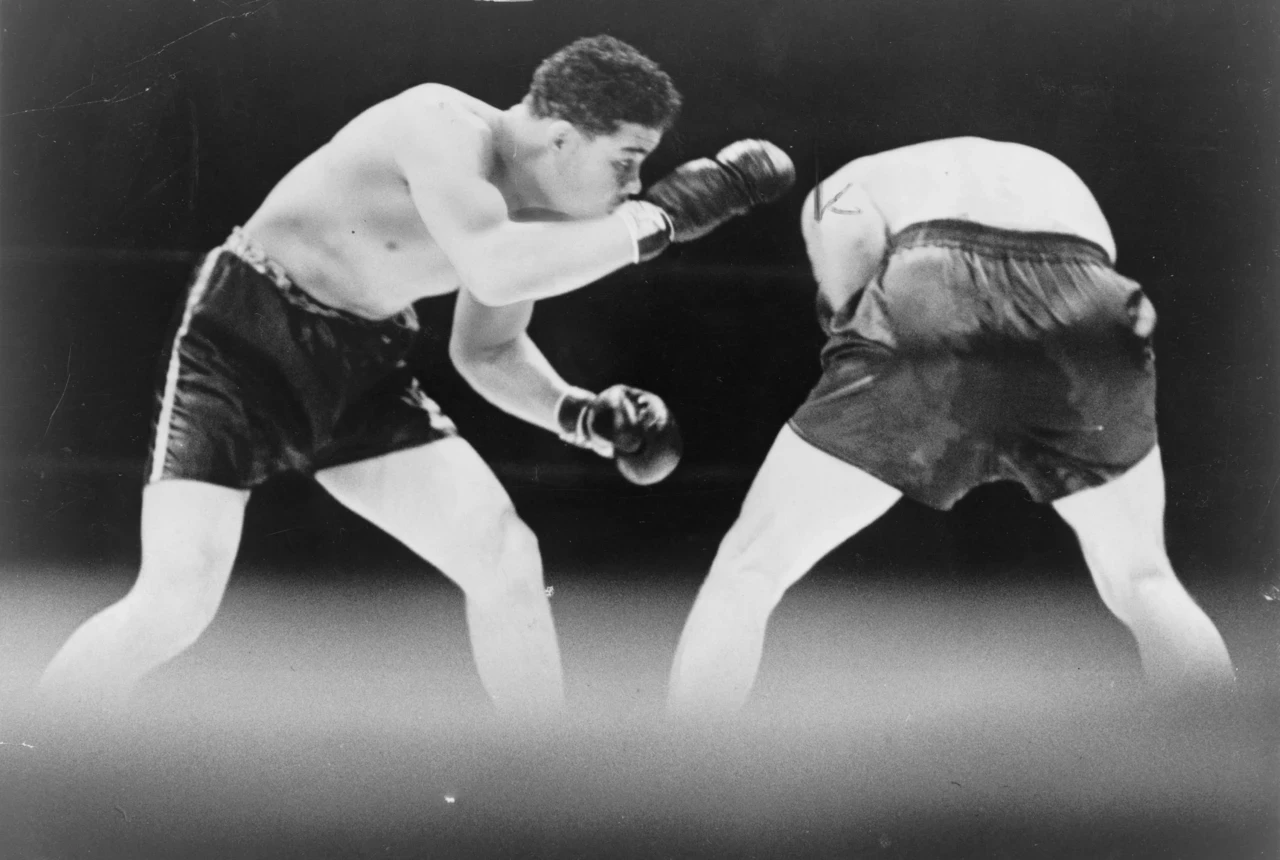

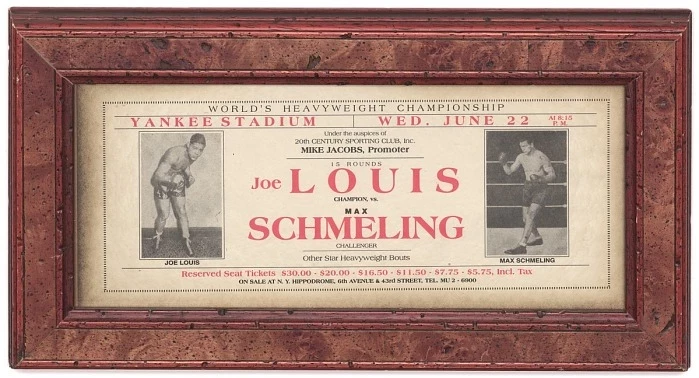

Joe Louis fought the most important match of his career in 1938. This was to become one of the most famous sporting events of all time. Two years earlier, in 1936, Joe had suffered his first professional defeat at the hands of German Max Schmeling.

Joe knew that he hadn’t trained hard enough, becoming complacent after so many victories. Bitterly disappointed at his lack of self-discipline, he was determined to fight a rematch – and win.

In Germany, meanwhile, Max Schmeling had become a national hero. The Nazi authorities seized on his victory against Joe Louis, citing it as proof for their racist doctrine of Aryan superiority. Nazi propaganda suggested that it was impossible for a black man to beat Schmeling.

The rematch between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling became doubly important – not only was Joe fighting to prove himself, he was fighting to prove the Nazi’s ideology wrong.

Poet Maya Angelou, who was a girl at the time of the match, later recalled what was at stake for the black community:

“If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help. It would all be true, the accusations that we were lower types of human beings.”

The historic rematch took place at New Yorks’ Yankee Stadium on 22 June 1938. The audience was packed with prominent figures, from actors like Clark Gable to FBI Director J. Egar Hoover. 100 million people tuned in on the radio, from all over the world.

Joe Louis won the match comprehensively, knocking Max Schmeling out in the first round. Across America, parties spilled into the streets. In his autobiography, Joe recalled:

'As we drove through Harlem, there were noisy, dancing crowds. Bands had left the nightclubs and bars and were playing and dancing on the sidewalks and streets. The whole area was filled with celebration, noise, and saxophones, continuously punctuated by the calling of Joe Louis' name.'

Following his defeat, the Nazis stopped celebrating Schmeling as a hero. He bravely stood up to the party, refusing to part ways with his Jewish manager, sheltering Jewish children and once even refusing an honour that Adolf Hitler had offered him.

Joe Louis and the Army

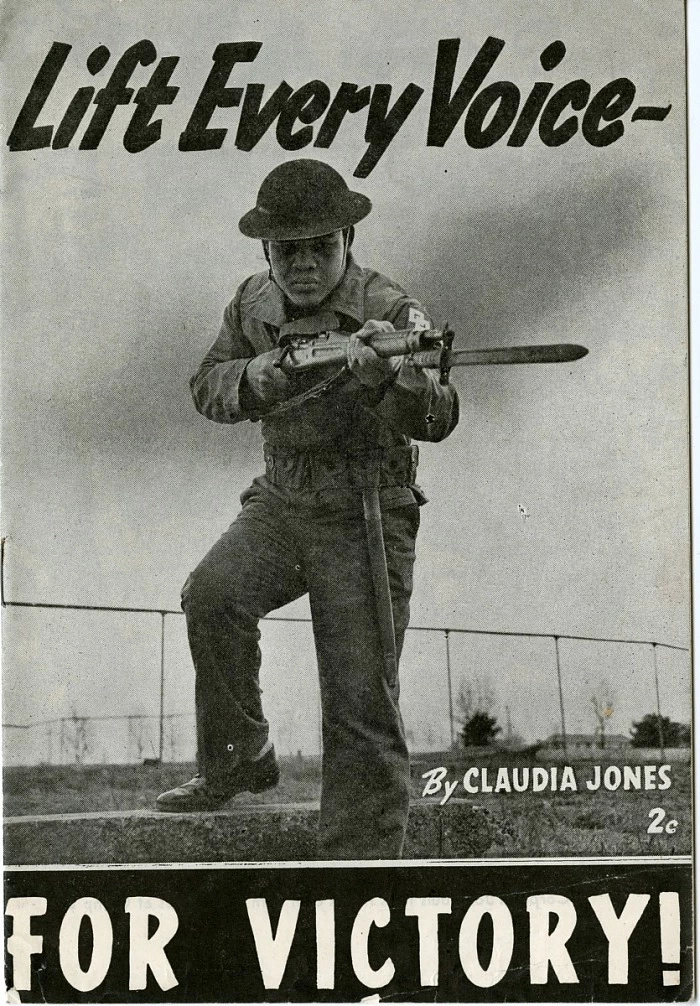

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Joe volunteered to enlist in the United States Army – a patriotic move that won him widespread acclaim. Joe’s celebrity status made him an ideal poster boy for the armed forces, and he was featured on a range of recruitment posters.

After completing basic training in Kansas, where he used his status to challenge discrimination against black troops, Joe was placed in the Special Services Division.

Rather than seeing active service, he was sent on a tour of army camps to entertain and inspire American troops. In this capacity he would eventually travel 21,000 miles staging 96 boxing exhibitions in front of two million soldiers.

(Image: wartime poster featuring Joe Louis, 1942 © National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Why did Joe Louis visit Bushy Park?

On Thursday 1 June 1944, this tour brought Joe Louis to London’s leafy Bushy Park – a far cry from venues like Madison Square Garden, where he had performed before the war.

In 1942, Camp Griffiss had been established at Bushy Park. It was home to almost 8,000 American troops. In 1944, General Eisenhower moved the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) to the Camp Griffiss. Here, much of the planning for D-Day took place.

It was just five days before D-Day that the park welcomed Joe Louis – still the world champion. Camp Griffiss had enjoyed many celebrity visitors over the course of the war, with visits from actor Clark Gable, dancer Fred Astaire and comedian Bob Hope. Glenn Miller even brought his orchestra to the park.

(Image: photograph of Joe Louis at Bushy Park, donated by John Cork © Bushy Park Archive, The Royal Parks)

Into the archive

In the Bushy Park archive, which has been compiled over decades by members of the Friends of Bushy and Home Parks and The Royal Parks Guild, there are some lovely insights into Joe’s visit.

A copy of the programme includes a brief biography of Joe. This reads:

'Since being in the Army, Joe Louis has been giving exhibition boxing for the benefit of his buddies stationed in camps in the U.S and U.K. While Joe has been built up as a champion of the ring, he is like any other GI sweating it out until he can get back home to his wife and baby girl in the good old U.S.A.!'

There were three other American boxers at the exhibition match, but Joe was the main attraction. The officials and referees were largely made up of American troops, but a Lieutenant from the British Army served as one of the Judges and a local man, Mr. Wilfred Smith of Teddington, served as timekeeper.

(Image: the programme for Joe Louis’ appearance at Bushy Park © Bushy Park Archive, The Royal Parks)

A report on the match published in the Daily Record read:

'Joe Louis looked good when he boxed yesterday evening before a crowd of about 7000 at Bushy Park. British Tommies, Air Force men, Canadians, plenty of American soldiers and at least 5,000 civilians were present. Louis boxed three rounds with Elzar Thompson […]'

British Private Joan Songhurst (nee Heyburn) was stationed at the park during the war, where she worked in the orderly room organising events and entertainments for the American troops. Recalling the day of Joe Louis’ visit, she later said:

'The day Joe Louis put on a boxing bout, we were allowed to take one visitor. My friend and I took two dear old grand-dads waiting hopefully at the gates. We got some funny looks from the Yanks, but it really made the old chaps’ day. They were delighted.'

Many of the servicemen and women stationed in the park would later look back and remember this visit from the world champion as a standout event of their time at Camp Griffiss.

What is the legacy of Joe Louis?

When Joe Louis died of cardiac arrest in 1981, President Ronald Regan organised for him to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honours. His one-time rival, the German Max Schmeling, contributed to the cost of his funeral and even carried his coffin. The two men had become great friends in later life.

(Image: Joe Louis photographed in 1936)

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC shares a poignant quote about Joe Louis:

'At the height of his popularity, people said Louis was “a credit to his race.”

In response, Boxing Hall of Fame sports writer Jimmy Cannon wrote:

“Yes, Joe Louis is a credit to his race — the human race."

Related Articles

-

Read

ReadBushy Park's own 'Masters of the Air'

When you’re taking a walk through Bushy Park it can be hard to imagine that the park has a fascinating military past.

-

Listen

ListenHidden Stories of The Royal Parks: Parks at War

In this episode David Ivison, historical researcher for The Royal Parks Guild, explains how the Royal Parks were used during the two world wars.

-

Read

ReadThe Camouflage School at Kensington Gardens

Following the start of the First World War, a school was founded in Kensington Gardens to develop camouflage techniques and patterns.