The Camouflage School at Kensington Gardens

In 1903, the first successful flight in a airplane was completed. Just over ten years later, when the First World War broke out, it was clear that the use of aircraft would change the way in which battles were fought.

For the first time, troops and their movements could be surveyed from the air, giving the enemy advance warning of the Army’s plans of attack. The British Army had to find ways to hide what they were doing behind the front line.

What happened at Kensington Gardens?

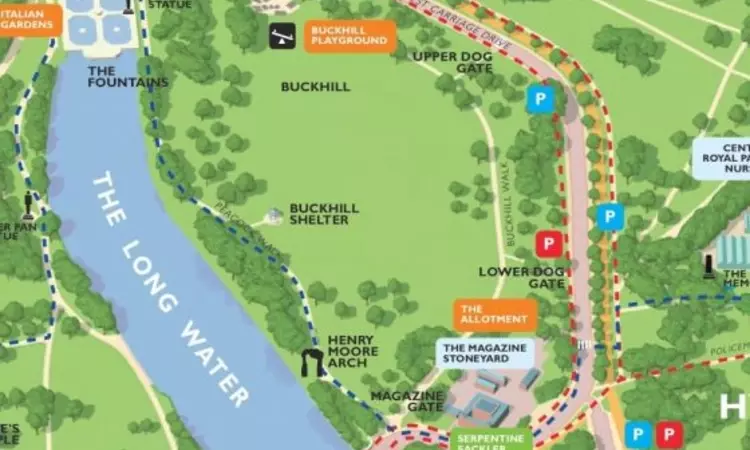

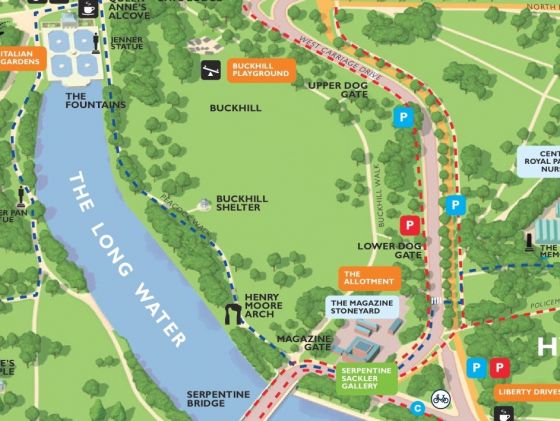

‘Camouflage’ - a French word - was a new idea for many in the British establishment. To demonstrate the importance of camouflage in this new kind of war, and to experiment and develop the necessary new techniques for concealment and disguise, a Camouflage School was founded in Kensington Gardens in March 1916.

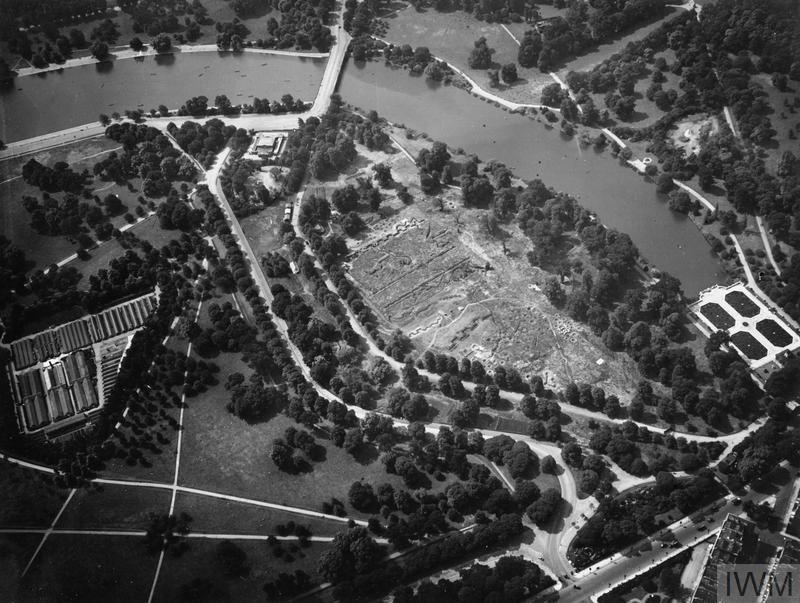

When the School was founded to explore the best ways to deceive the enemy on the battlefield, Kensington Gardens already looked like a warzone. Since late 1914, the Army had been using the park as a place to practise digging trenches.

“A soldier who goes to war these days without knowing how to dig trenches has about as much chance as a rabbit who is born without the instinct of going to ground.”

Extract from a letter on the subject of trench practice in Kensington Gardens in November 1914

As there were already trenches in the park, it was the perfect place to work out ways to camouflage them from the air. Those working at the Camouflage School came up with many different ideas for disguising, concealing and misleading the enemy. Some of these ideas never made it to the frontline. Others are still used by the military today.

The 'artist-officer' at war

The Camouflage School employed artists, set painters, theatre designers, sculptors, photographers and craftsmen to develop techniques for disguise.

With their experience of creating lifelike images on flat surfaces, painters had the skills to mimic tanks on canvas, while set designers, who were used to making hundreds of props for a show, thought nothing of creating armies of papier-maché heads to poke over the trench parapets and attract enemy sniper fire.

Inspired by nature

People at the forefront of the development of camouflage looked to nature for ideas.

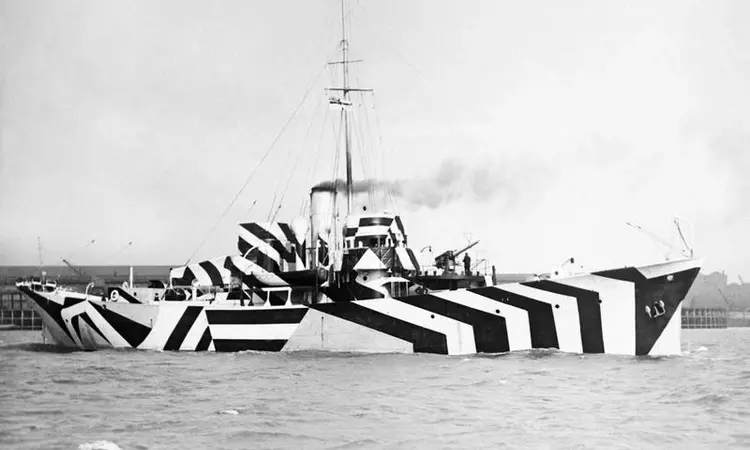

The British zoologist John Graham Kerr wrote to Winston Churchill in 1914 stating:

“It is essential to break up the regularity of outline [of ships] and this can be easily effected by strongly contrasting shades … a giraffe or zebra or jaguar looks extraordinarily conspicuous in a museum but in nature, especially when moving, is wonderfully difficult to pick up.”

The inspiration of the natural world was clear in the 'dazzle' technique that was developed. Large black and white stripes were painted on potential targets, like ships, to make it difficult for the enemy to work out its size, direction and speed.

Women at War

Many women worked at the Camouflage School in Kensington Gardens. Some wove camouflage nets, while others worked as secretaries to high-ranking officials.

New Research

The Royal Parks played an important role in the First World War - not just in Kensington Gardens. We continue to research this important part of our history and will update the information we share online as work develops. Watch this space!

Related Articles

-

Listen

ListenHidden Stories of The Royal Parks: Parks at War

In this episode David Ivison, historical researcher for The Royal Parks Guild, explains how the Royal Parks were used during the two world wars.

-

Listen

ListenWomen in The Parks

In this episode, recorded for Women’s History Month, we look at some of the great women associated with the parks.

-

Read

ReadWomen of The Royal Parks

Women's History Month takes place each March, highlighting the contributions of women and their achievements.